FINANCIAL TIMES

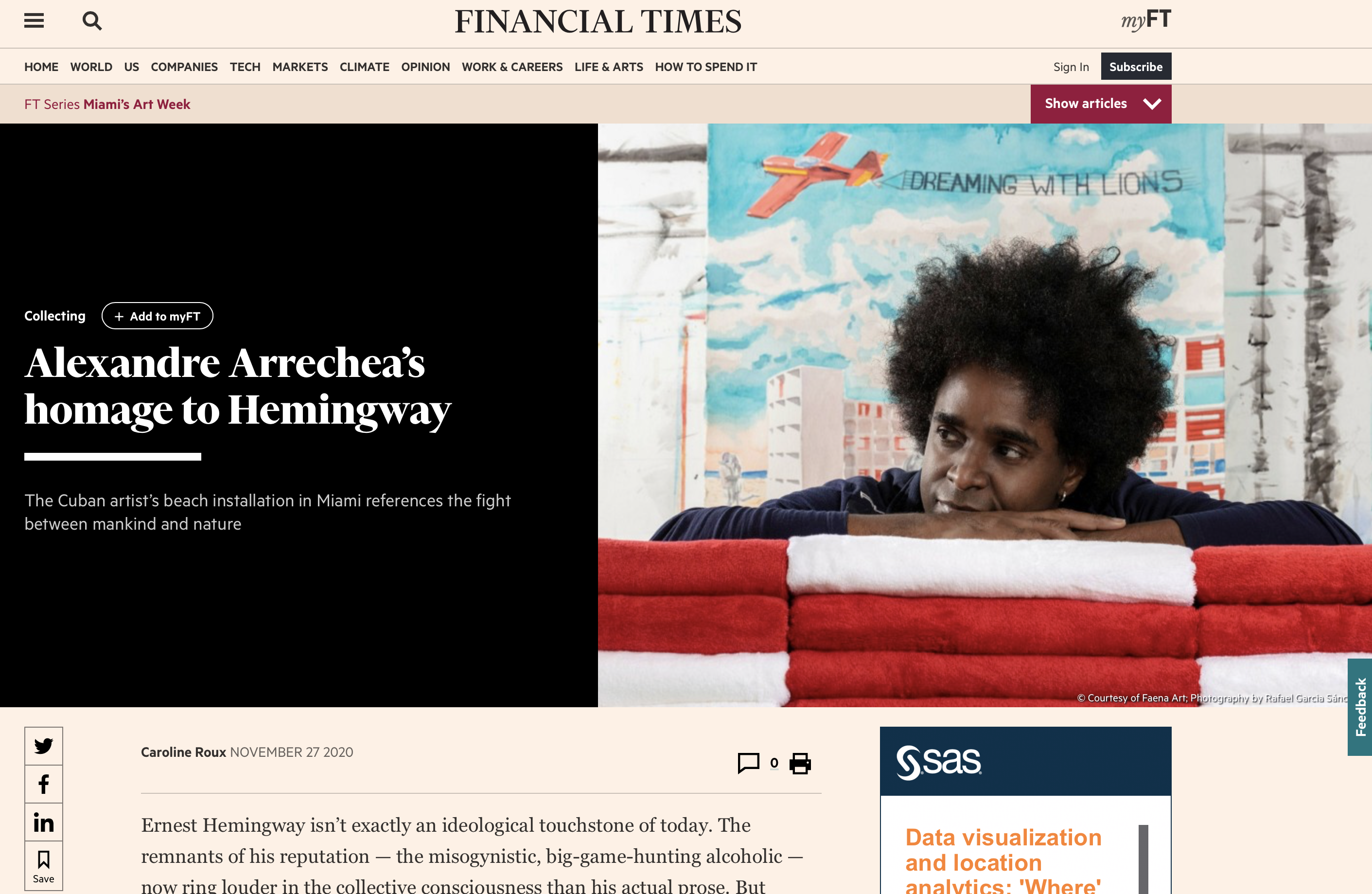

Ernest Hemingway isn’t exactly an ideological touchstone of today. The remnants of his reputation — the misogynistic, big-game-hunting alcoholic — now ring louder in the collective consciousness than his actual prose. But Santiago’s soliloquy from The Old Man and the Sea popped into the Cuban artist Alexandre Arrechea’s head in early lockdown, and inspired an artwork that will open to the public on Sunday on Miami Beach. For those who haven’t read Hemingway’s lean writing for a while, the novella tells the story of an elderly fisherman, Santiago, in Cuba who sails into deep Gulf waters to end a long run of catch-free excursions. He lands an enormous marlin, which is gradually consumed by sharks as he gets it back to the shore. “It’s a story of resilience, about being no longer in control, but refusing to give in,” says Arrechea. “For me, the last sentence is like a rebirth, as Santiago dreams back to his youth.” While the novella’s final line looks at a sleeping Santiago, and says “The old man was dreaming about the lions”, the artist has taken some syntactical liberties. The installation is called “Dreaming with Lions”.

Alexandre Arrechea was born 50 years ago in the city of Trinidad, in Cuba. Its powerful architecture, including the neo-baroque Plaza Mayor, has influenced his work ever since. Reflections on the political and social meanings of architecture, and objects derived from the architectural world are at the core of his practice, while the failure of Cuban’s socialist dream and the force field of a heavy-handed surveillance state (which now through technology includes the whole world rather than any individual country) run along its edges. In Miami, the city he has called home since 2015, he has created an installation in laminate and wood, 10ft high and 62ft long — a wall that winds around like a rotunda, or a library. Or perhaps a barricade. In it, beach towels (well, we are in Miami) are printed with words from Santiago’s soliloquy — “Man can be destroyed but not defeated”; “Now is no time to think of what you do not have. Think of what you can do with what there is” — that he sees as relevant to these times. “The Old Man and the Sea is partly about the fight between man and nature, and this year we have no longer felt in control of our destiny in the face of the pandemic,” Arrechea says.

The work is supported by Faena Art, a non-profit organisation that mostly commissions site-specific and time-based works in Buenos Aires and Miami. It’s named for its primary instigator Alan Faena, the Argentine hotelier and real estate developer, who has built both the Faena Forum cultural centre in Miami, as well as turning the 1948 Saxony into one of the city’s most lavish hotels — and calling that the Faena too (it opened in late 2015). “Alexandre is an artist who often works in public spaces,” says Alan Faena, “and we wanted a piece of work that reinforced our union with the local community — both in terms of those artists who live and work here and the public.” The work is likely to be up for just one week. “I have learned that temporariness is part of the structure of my work,” says Alexandre Arrechea. “That’s not a problem. Especially in terms of public projects, if something sits there for 20 years, the meaning probably gets lost or changes.”

Arrechea, apart from being known as the third member of the now-disbanded Havana-based artist collective Los Carpinteros (he was with them from 1992-2003), gained international visibility for a glimmering series of public sculptures which appeared in New York’s Park Avenue for six months in 2013. Mutated models of 18 of the Avenue’s most iconic buildings, including the Empire State, Flatiron and Chrysler Buildings — stamped from steel and inserted into primary-coloured stands — were presented at street level, and the public were invited to touch them, and even spin them round. “I wanted to bring the skyscrapers to the tips of people’s fingers,” says Arrechea. “I wanted people to make them move.” The message seemed ambiguous — perhaps that these monuments to capitalism and power might one day become curiosities of human hubris, the archaeological remnants of a twisted past. At the Coachella festival in 2016, he went on to present four supersized and teetering acidic yellow chairs-like structures, adorned on their tops with scaled-down buildings. “It was my reaction to the US’s slow response to Hurricane Katrina,” he says. “I suspended the buildings in the air to say that we should build in a safe space, not in the levees. I wanted to make people think; to put this idea in the minds of the young.” Arrechea’s Miami project is also scaled down. “In June, we thought we could start the installation in the Forum and move through the lobby of the hotel and out to the beach,” says the artist, of the direct pathway that exists between these points. “But in the end the conditions were too unstable. At least on the beach, we know the public can come, and look, and be socially safe.”

What concerns him perhaps more is the situation of artists when Miami’s Art Week is over. “Faena is a great champion of us all, supportive both intellectually and financially. But every year when Art Basel is here in December, we feel we’re being taken into account. Then afterwards the artists fade into the background again.” Not so, however, with Cubans, which brings us back to the subject of control. “That is an altogether relationship,” laughs Arrechea. “For me it’s been an important field of study, the relationship of Cubans with this city. That’s about control, and the Cubans have it.”