CORNERS

Corners

Can a city wear a mask? Or be a mask?

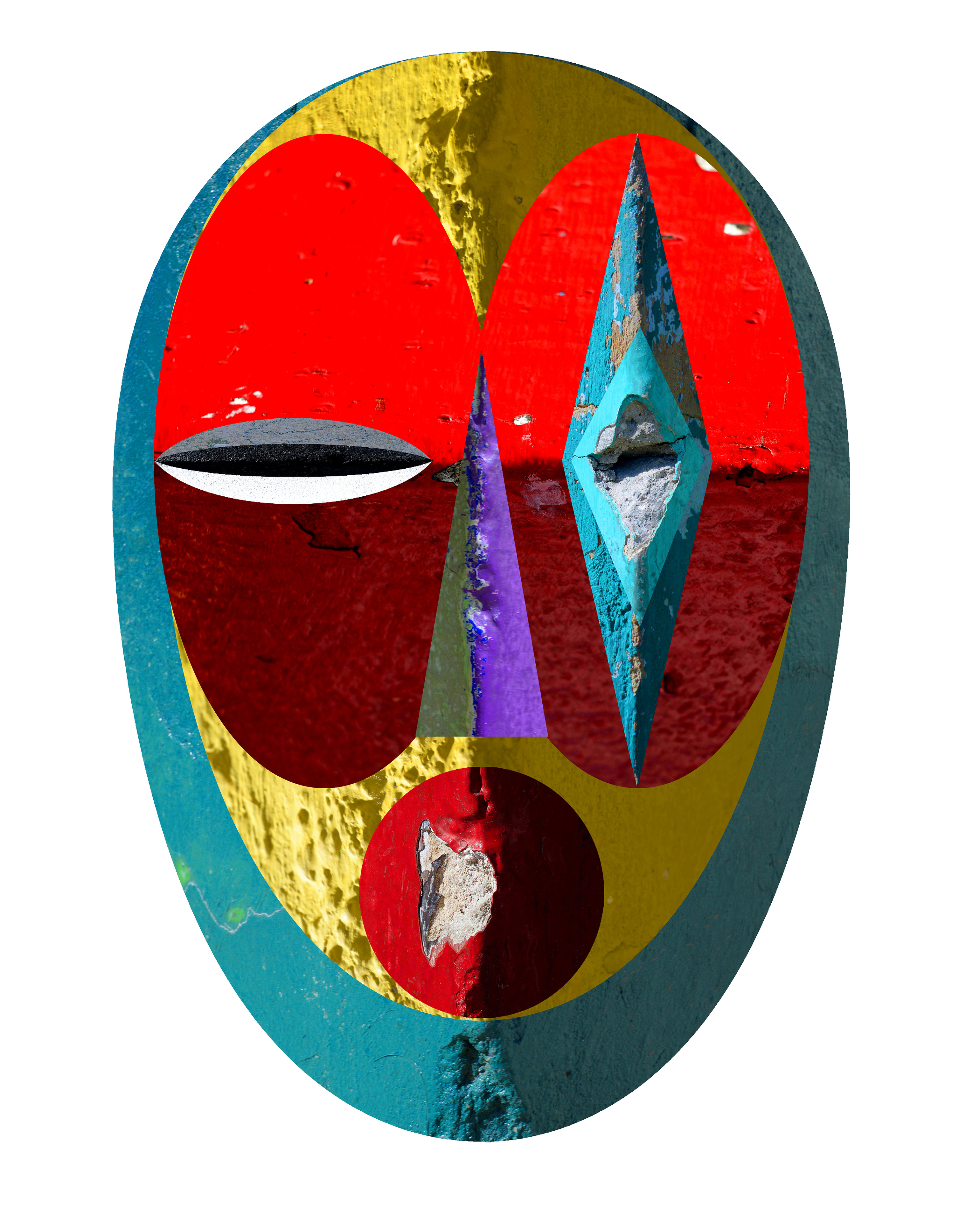

These questions come to mind as we seek to reconcile our natural propensity to read these visual impressions by Alexandre Arrechea—which the artist admits “bears reference to facial anatomies, especially those of tribal masks”—with the artist’s stated purpose to capture aspects of the character of Havana, Cuba. Is Arrechea shrewdly alluding to the strong African elements in Cuban culture? Is he capturing glimpses of the city and its architecture through virtual keyholes? In fact who is actually wearing the mask? The city? Or us as furtive observers of its daily comings and going?

The recurring compositional format in these works-conceived from superimpositions of architectural photographs by the artist—is the presentation of corner elements that tend to bifurcate the scenarios within each mask form. Arrechea sees these bifurcations as Corners: points where “where two buildings that might be considered emblematically antagonistic are forced into an unnatural co-existence.” Through this intervention he “seeks the merging between excluding worlds, thereby forging a new identity.”

Arrechea’s Corners project can be viewed in tandem with work by other artists from Cuba, who have engaged the physical aspects of its leading city. Ernesto Oroza has chronicled what he dubbed the the Architecture of Necessity as a celebration “the efficiency and ingenuity of Cuban citizens…and their approach to self-made solutions for their everyday needs.” And there is Coco Fusco’s elegiac video tour of the Plaza de la Revolucíon, empty of people, revealing its essential nature as dispirited expanse of asphalt lacking the passionate energy that crowds bring to the space.

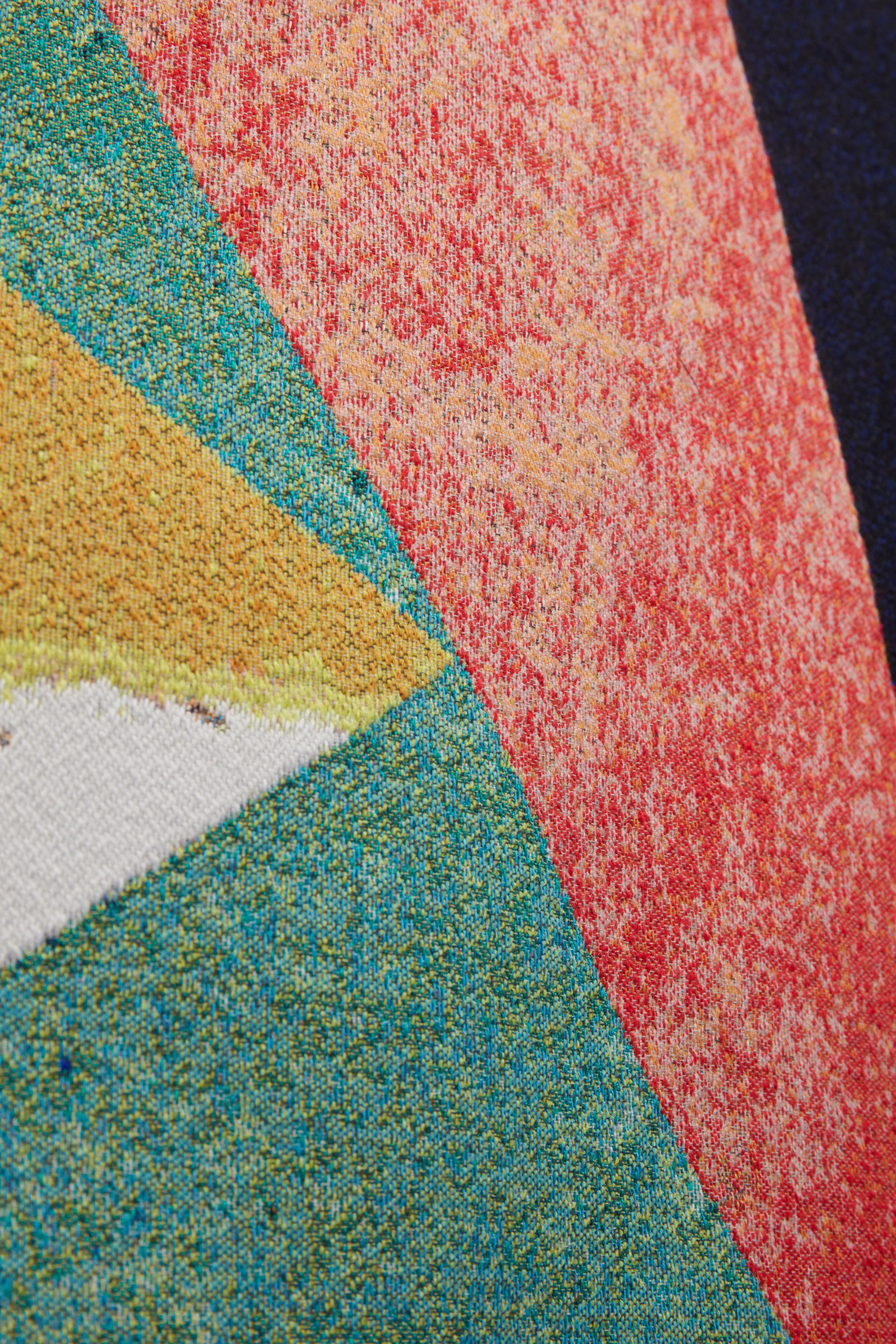

The titles of Arrechea’s works indicate localities (At the Train Station, or Black Eye in Vedado—the business district of Havana, both 2019), suggest personal states of being (Nothing to Do, Two Cops Wandering Around, or Black Smile, also 2019), or subtle commentary (the tapestry Confusion in Centro Havana, Unpopular Measures, Eight Different Problems, or even New Theatre, 2019). In a comparable way Carlos Garaicoa’s series of tapestries of sidewalks, Fin de Silencio, have various slogans imbedded in them that provide tacit and implicit commentary about the state of pedestrians living under the current political system: “Cambio,” “La General Tristeza,” “La lucha es de todos, de todos es la lucha.”

Corners remind us that Arrechea has consistently used architectural forms and motifs to convey emotional and political states over the last decade: a modernist building sitting on a chair (Conspiracy, 2007), arenas and buildings with no access or egress (Arena, 2007 and Home, 2008), bridges that go nowhere (Limite improvisado, 2007), cities whose layouts are inescapable mazes (Blind City (From the Series…), 2007). And then there was his 2013 tour-de-force installation No Limits on Park Avenue in New York City, which featured familiar architectural monuments that are improbably coiled, sitting on spinning tops, cranked up or down by levers. What makes these images all the more tantalizing is the fact that often the buildings lack means of egress emphasizing Arrechea’s critique of architectural pretensions and intrusions. In Corners the architectural forms are less recognizable. We get only glimpses of the whole structure through the peephole views that are framed by the contour of the mask forms.

If a corner is “a point at which a derivative of a function is discontinuous” or an intersection of two objects where both terminate,” in these works “two buildings that might be considered emblematically antagonistic are forced into an unnatural co-existence.” So there is an aspect of the sinister in these corner meetings (where in some quarters troublesome occult forces are believed to hide). But as Arrechea notes these are corners “of schools, theaters, gas stations, markets, and police stations” that “talk…observe… listen, laugh, and remain silent”

But in addition to marking intersections, each form in Corners looks through to various spatial arenas. The most direct are the two blocks/buildings seen at their corner edges in Two Cops Wandering Around. Arrechea has divided the space into a green segment and a blue one. The darker greens of the two planes of the form on the left introduce a chromatic compatibility with the background, while the yellow and pink planes on the right provide a complementary contrast to the blue background. There are intimations of the studies of color contrasts and complements of Josef Albers with a textural interest that results from the process making the paper surface. A more complex presentation can be seen in Black Smile, where the flat space of the darker green oval plays off the lighter one in which a pink pyramid floats. They resemble ocular elements that function in concert with the modified trapezoidal “mouth,” framing a fragment of a glass façade and a more textural red/ orange one. Here “color and diverse surface finishes are the primary protagonists” as a form of “social engineering” creates what Arrechea describes as “new loyalties.”

Such “new loyalities” can be glimpsed in the diamond shapes fragments that suggest the black and yellow/green eyes and white and red triangular mouth in Black Eye in Vedado. Again the background is divided into two colors—blue and black—that continue the exploration of chromatic contrasts as seen in Two Cops Wondering Around. The landscape fragments become a bit more coherent in Arrechea’s tapestry Confusion in Centro Havana where the interlocking pyramids in green, white, red and ocher shades play off the green trapezoid on the left half, where the green structure divided at the middle on the lower portion of the composition demonstrates the visual impact of green on yellow as opposed to shade of red. Eight Different Problems shows a formal and spatial complexity comparable to that of Black Smile: Here Arrechea is the most specific in his visual reference to masks: he frames the two oval spaces that contain a black landscape with a red “sky” with a ocher heart-shaped contour so that we can’t help but recognize the convention of Kwele masks from Gabon. A double isosceles triangle in pink hovers against the horizon on the right, while a gray, black and white elliptical one blinks at us and a green triangle and round porthole mouth complete the facial inferences.

Perhaps the source of all these spatial and formal gyrations is the French modernist painter Paul Cezanne, who declared his intention to “treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone,” because he believed “nature for us men is more depth than surface.” In this series of works Alexandre Arrechea provides the viewer with more than the surface of the character of Havana. By eschewing obvious representational elements he encourages us rather to form a vision of the inner character of the place through the experience of “symmetry, proportion, lighting and shadows.”

Lowery Stokes Sims

New York

January, 2019